Remembering Family Stories

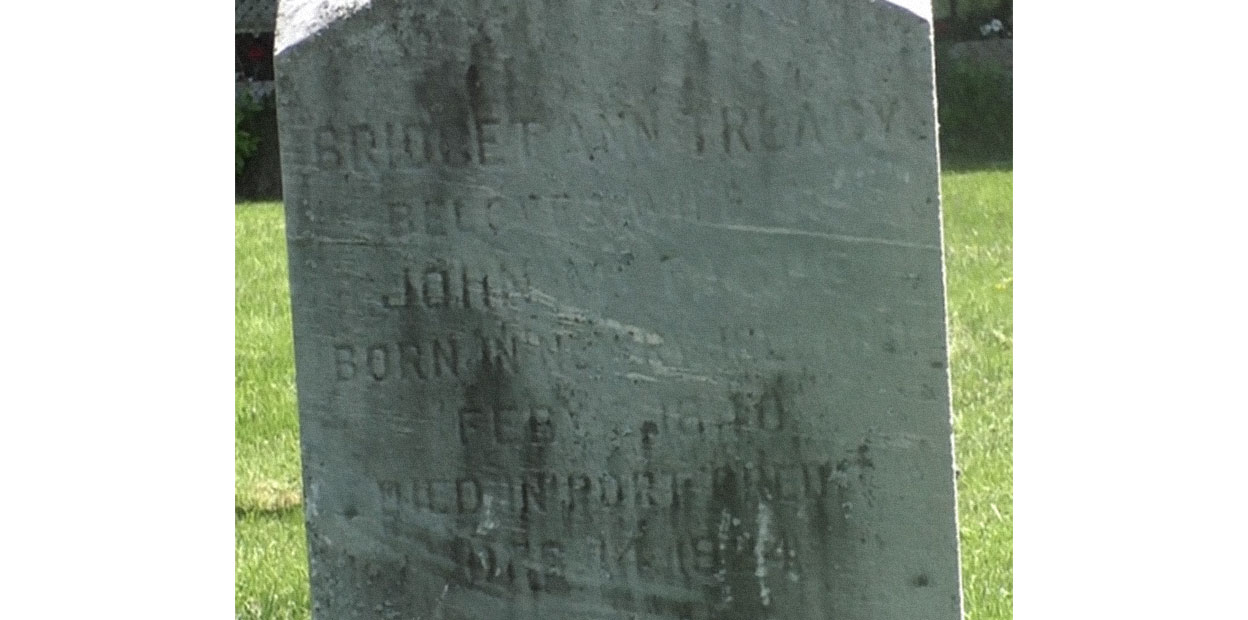

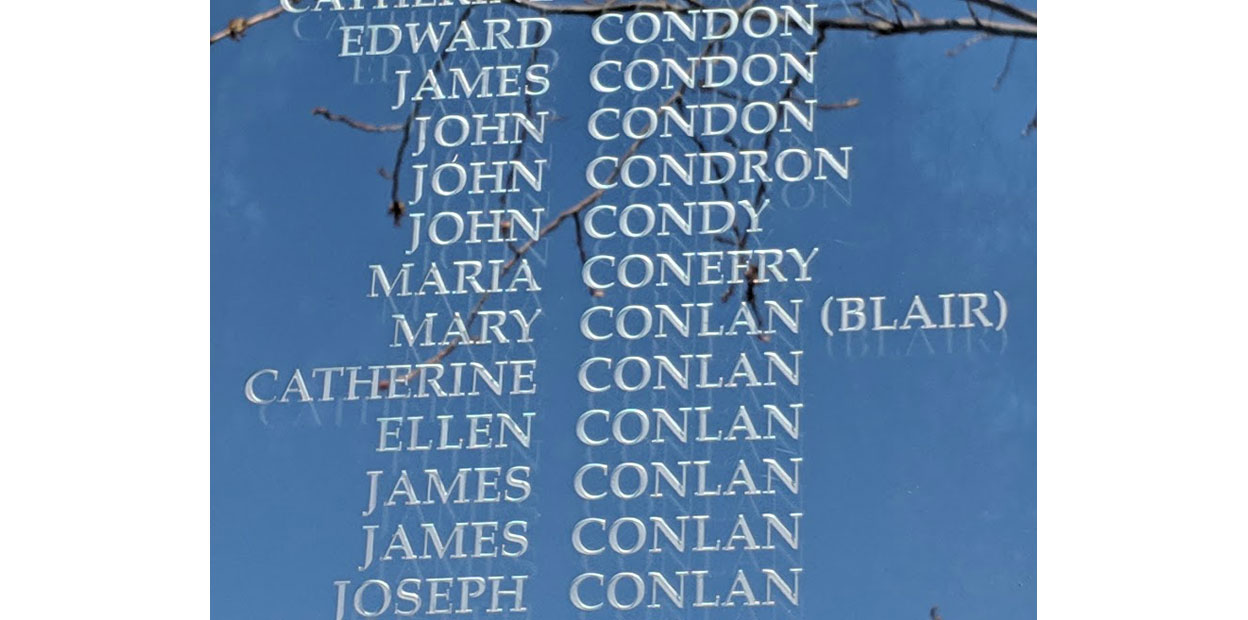

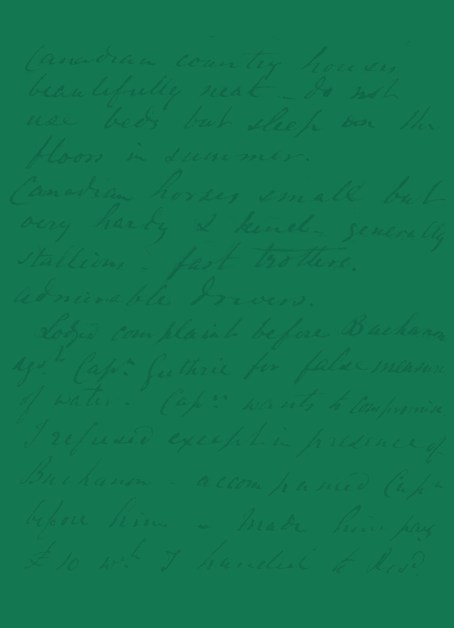

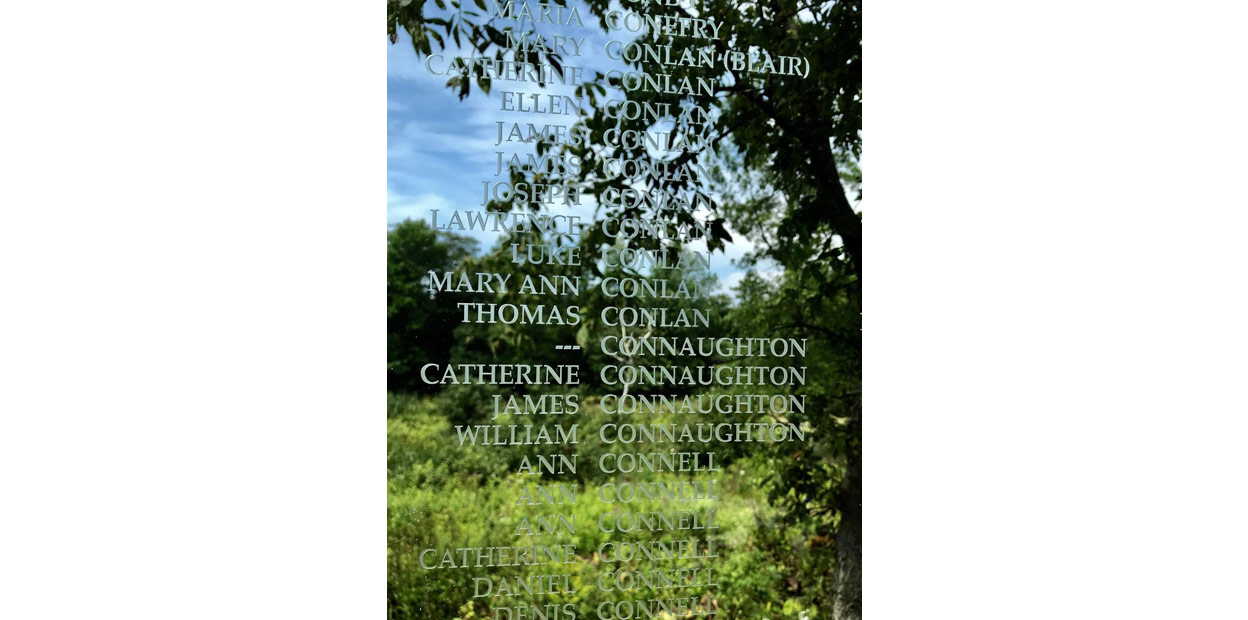

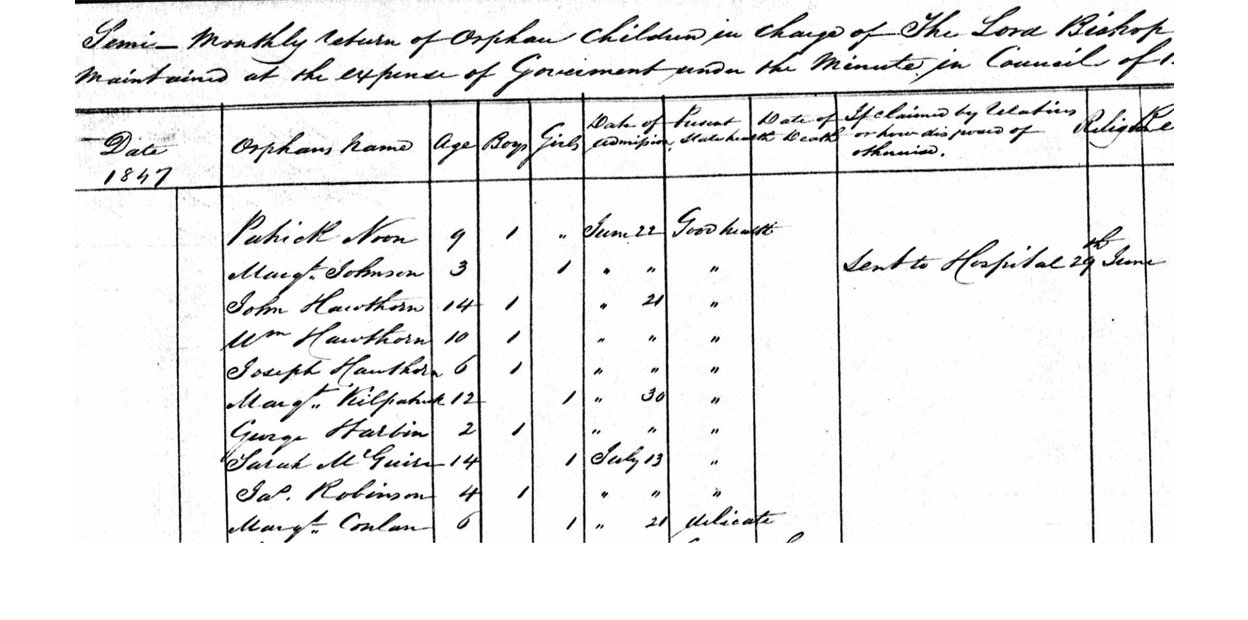

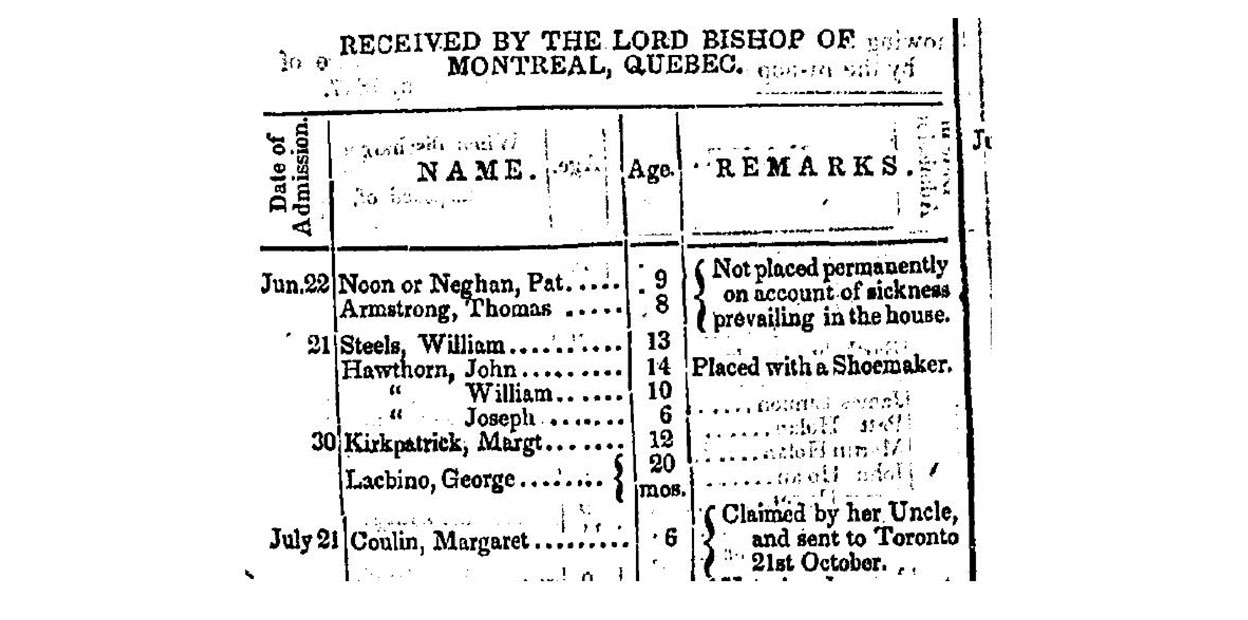

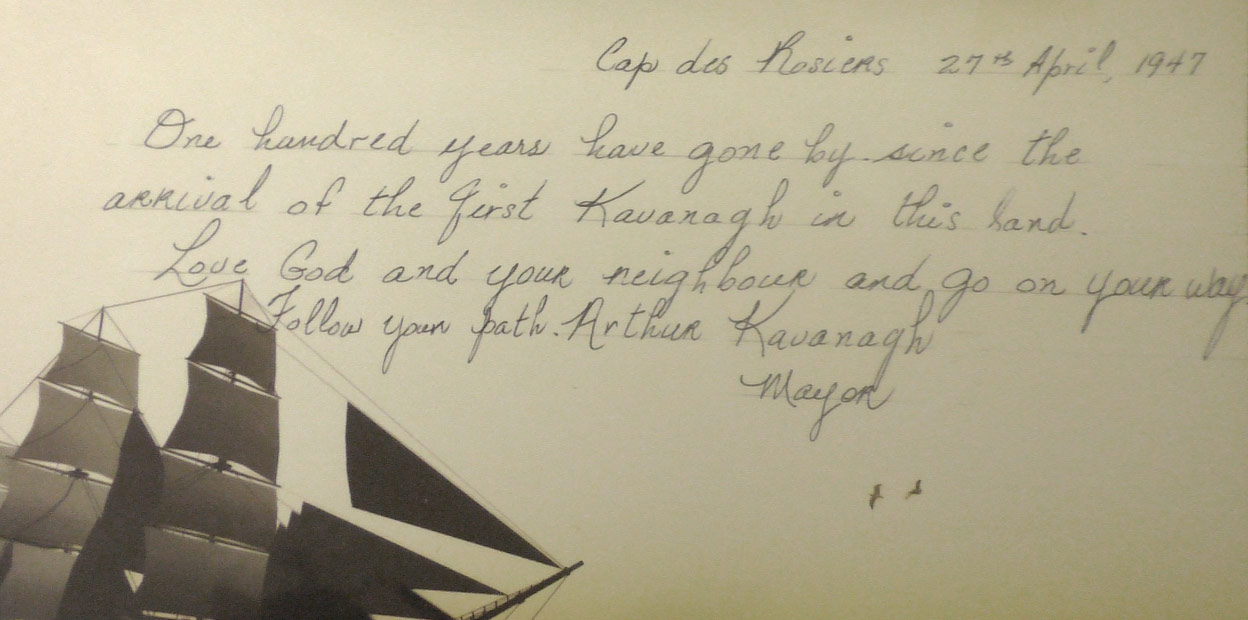

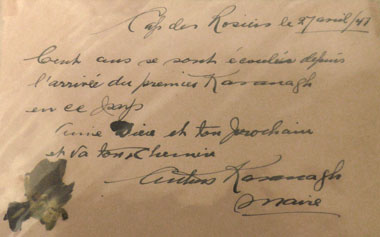

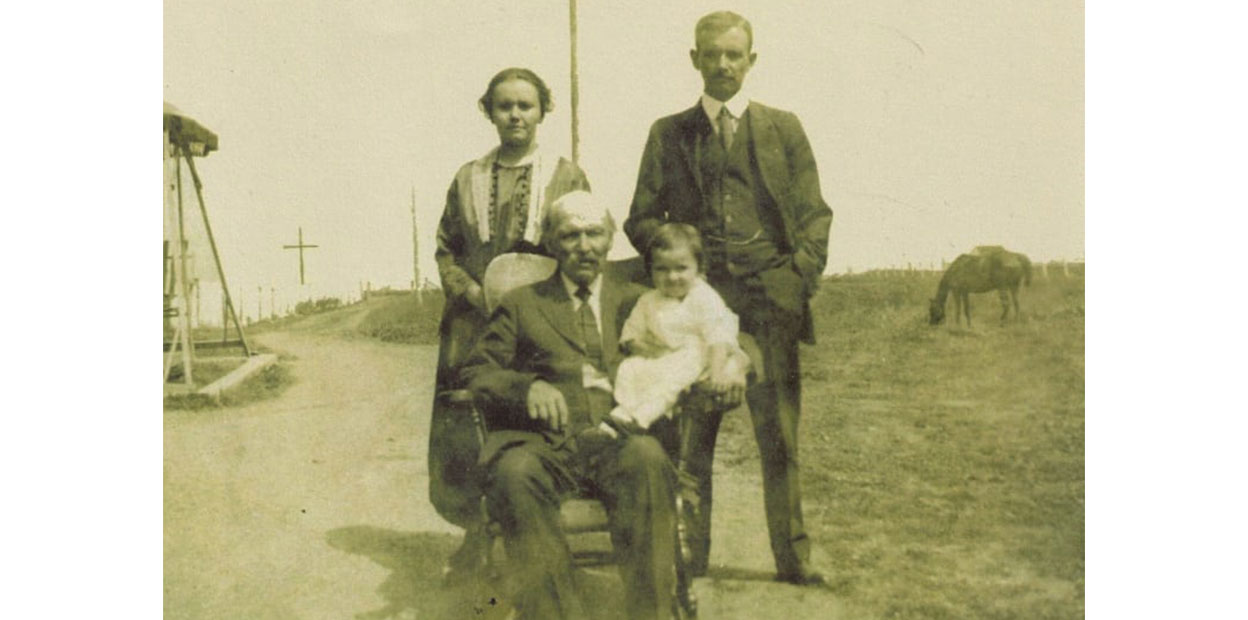

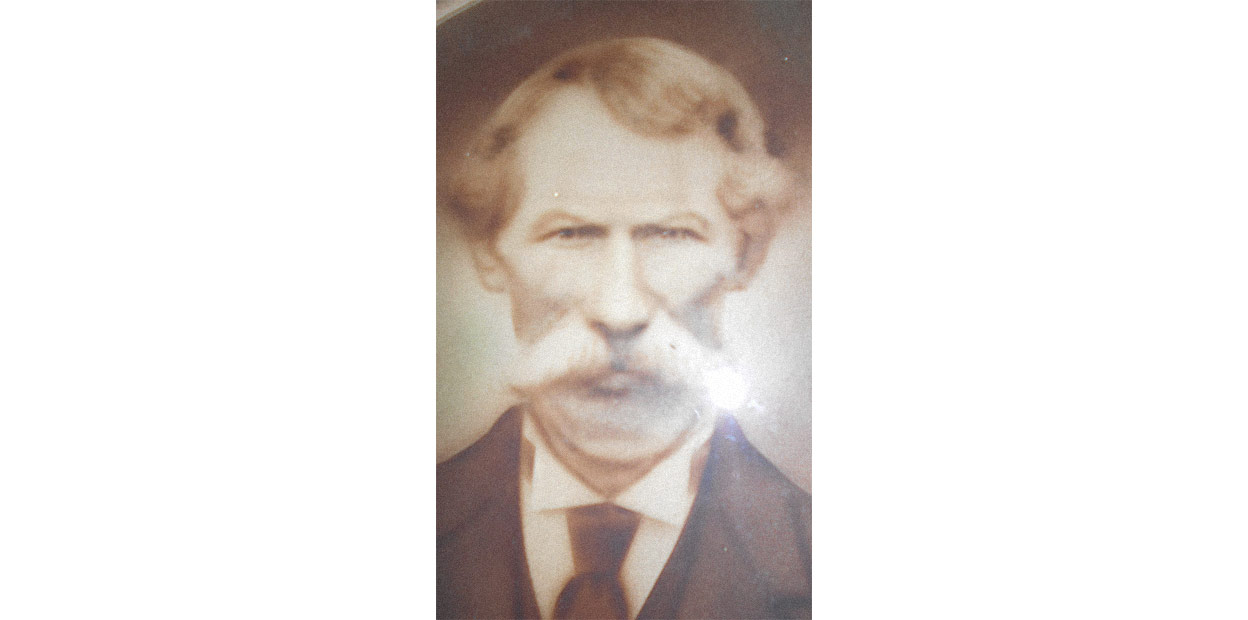

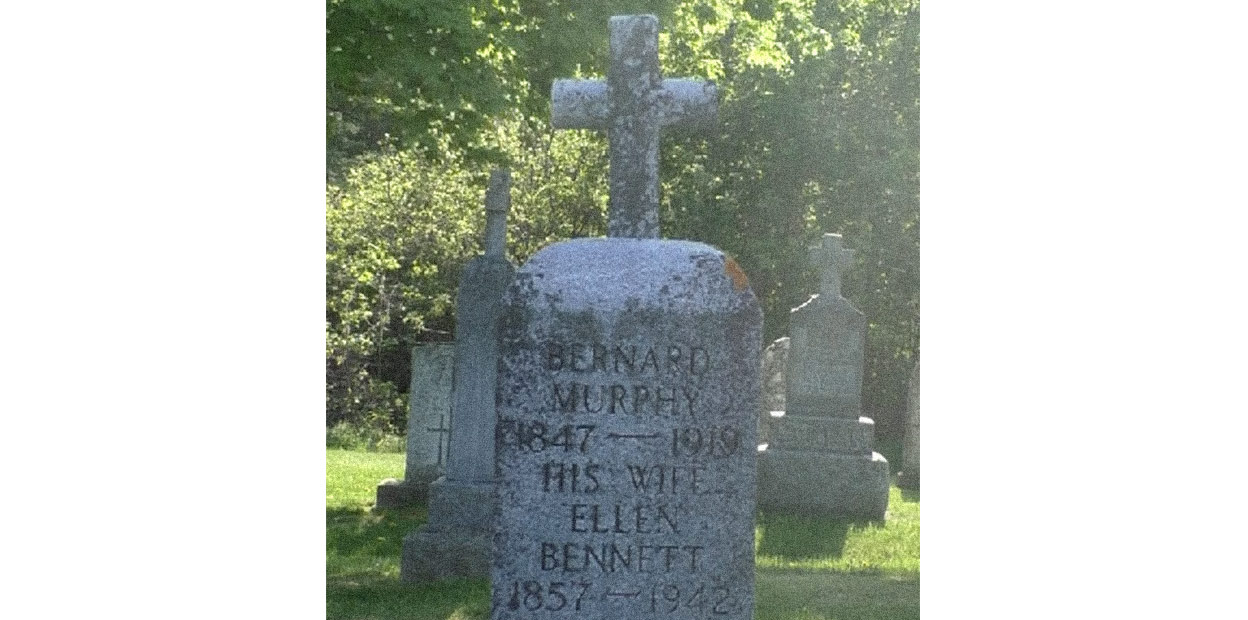

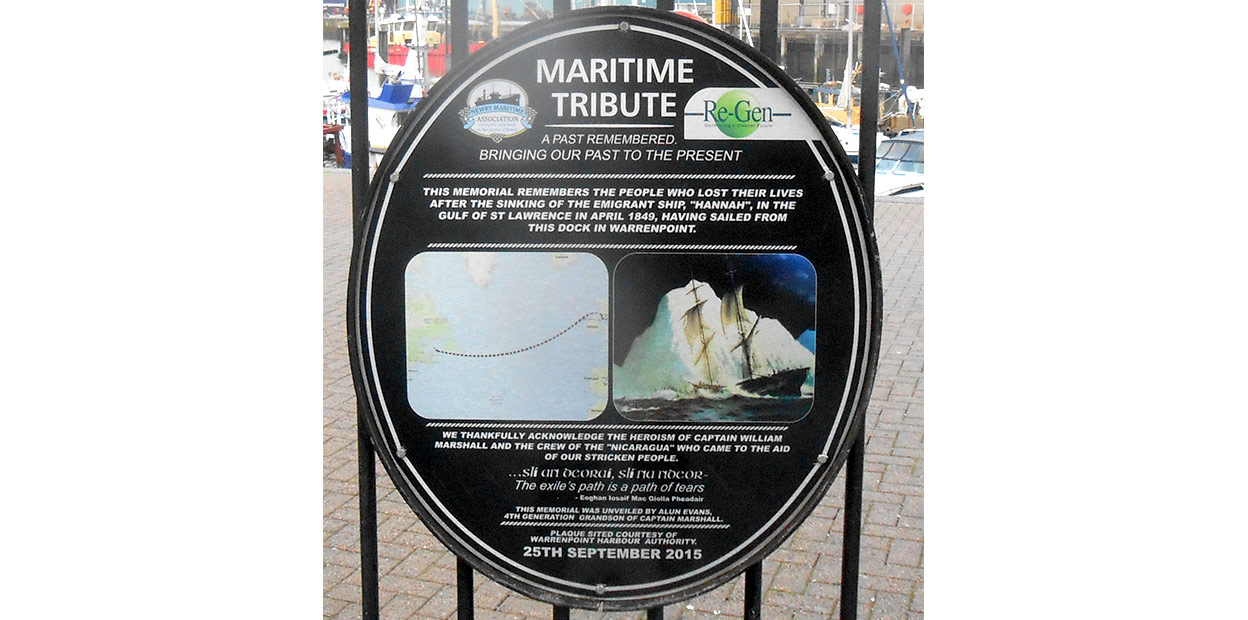

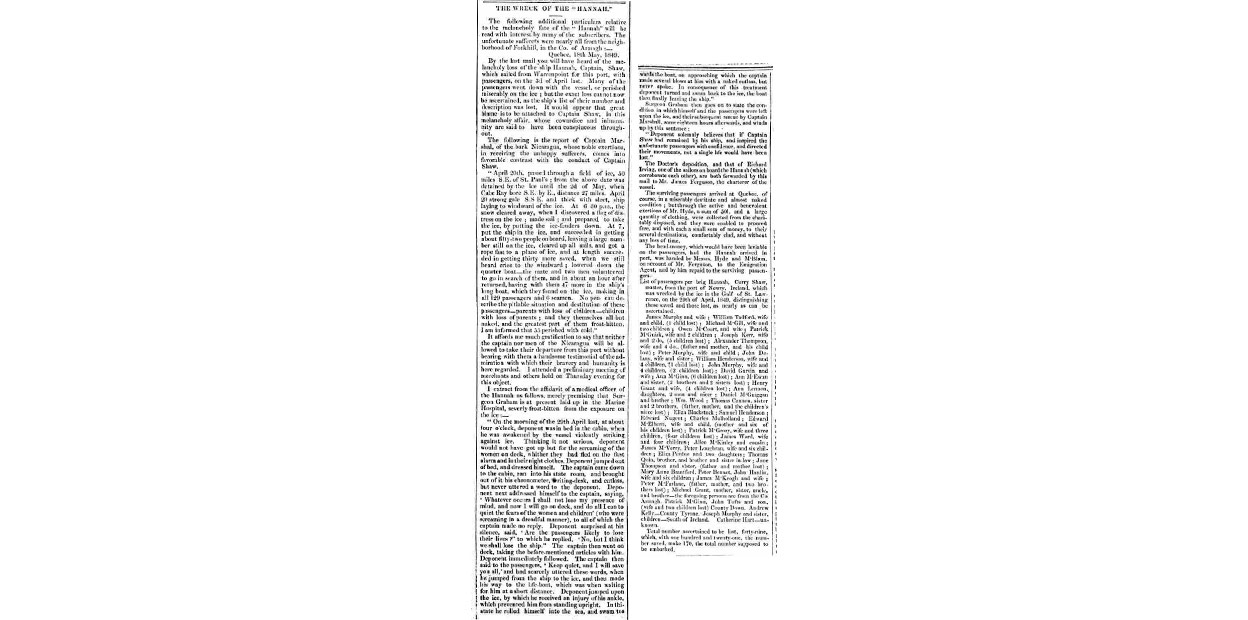

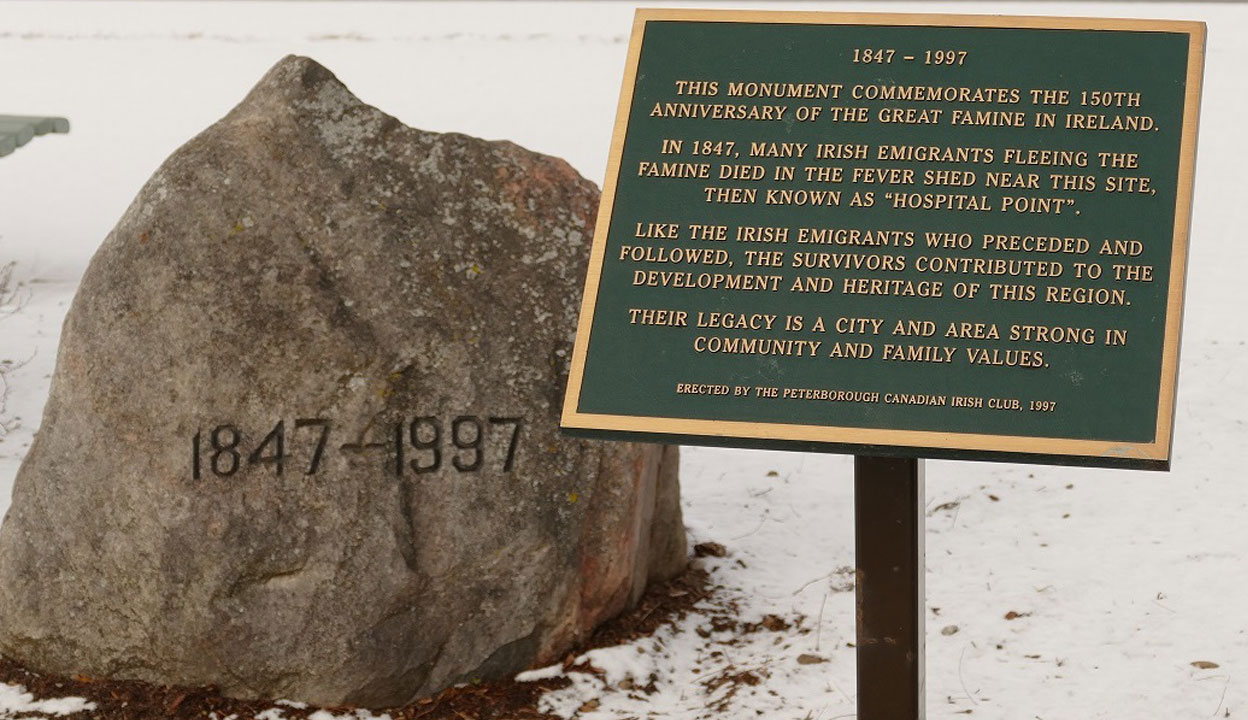

Remembering Family Stories is the exhibit’s final theme. It brings together the living descendants of Famine emigrants such as Bridget Ann Treacy, Margaret Conlon, Sarah Kaveney, and Rose and Barney Murphy who survived shipwrecks on board the Carricks and Hannah to start new lives in Canada and Ontario. It emphasizes issues of ancestry, memory, and the importance of migrant belongings, keepsakes and mementos brought to Canada by Famine emigrants from which their descendants help create their own sense of belonging. They share precious family heirlooms that have been passed down through generations and create a living link with the past. Their family stories and memories also provide an example of how important it is for migrant groups to remember where they have come from, especially when they arrive under traumatic circumstances. Famine Irish ancestors are also recalled through dramatic performance, Gaelic language speech and song, tattoos emblazoned on the skin, and endeavours to find emigrant graves. Ultimately, they symbolize the perseverance of Famine emigrants whose self-reliance provides a sense of inspiration for their descendants. Indeed, they mark an inheritance of ancestral female resilience.